Core Massage and Bodywork for Men: Pelvis, Hips, Thighs, Low Back and Abdomen

The Male Pelvic Floor

Men are often unaware of their pelvic floor, or may not understand its relationship and importance to core, pelvic, genital, sexual, and voiding health. It is often challenging to sift through a range of sources to find comprehensive information that is understandable, practical, and most importantly, accurate. Many men can attest to how confusing, contradictory, and frustrating an endeavor this can be.

"I was particularly drawn to you because you have a lot of experience and you have dealt with an area of the body, particularly mens bodies, not a lot of mainstream physicians put much focus on. And most typical massage practitioners don't know how to work in this area therapeutically."

Even physicians, manual therapists, athletic trainers, personal trainers, yoga instructors, martial arts instructors, and other healthcare practitioners frequently have a poor understanding of the pelvic floor's contribution to the core, or its relationship to the pain, dysfunction, concerns, and goals of their patients or clients. Furthermore, many of these professionals assume that the pelvic floor is far more, or only, relevant and important to women's health, and are not familiar with the substantial and increasing body of evidence which confirms that it is equally critical to men's health. Quality education and training programs devoted to the pelvic floor — especially the male pelvic floor — are few to non-existent, and therefore these professionals usually lack the knowledge and skills to recognize, evaluate, and treat or work with the male pelvic floor and pelvic floor-related issues.

This is an immense loss for the many men who are seeking to learn more about their bodies, or who are trying to find someone who can understand their condition, explain their symptoms, and offer them helpful tools, useful strategies, and appropriate treatments.

Section titles within this page are:

The Pelvic Floor and its Relationship to the Core

Pelvic Floor Anatomy and Function

The Pelvic Floor's Role in Genital, Pelvic, and Core Pain and Dysfunction

The Respiratory Diaphragm and its Relationship to the Pelvic Floor

Giving the Pelvic Floor Muscles the Attention they Deserve.

Hover over the citation numbers to see the source, or scroll down to the bottom to view the full list.

The Pelvic Floor and its Relationship to the Core

"Everything on my left side was loosened after last time [inguinal area, spermatic cord, groin] and my left testicle hung lower."

While definitions of the core can vary from narrow to broad — as noted on the previous page — there is widespread agreement that the pelvic floor muscles are a critical component no matter how it is defined. Many functions of the core would not be possible, or would be much less effective, without the contribution of the pelvic floor. As Yuan and Bevilaqua clearly state in the journal Current Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Reports, the pelvic floor is involved in controlling and coordinating motion around the hip, sacroiliac joint, lumbar spine, and trunk [1]. Gordon and Reed add that the pelvic floor musculature has important roles in respiration, in the generation of intra-abdominal pressure (a key function of the core), and as a primary driver of forced expiration during vigorous activities such as heavy exercise, robust movement, sneezing, coughing, or blowing [2].

"It was huge, the energy that came up last time. The whole middle part of my body is waking up and I appreciate being in my body in ways that I haven't in the past. The last session, and the work in general — I really appreciate it."

These muscles at the bottom of the pelvis function synergistically with other parts of the core musculature, particularly the transversus abdominis in the abdomen, the multifidus muscles of the lumbar spine, and the respiratory diaphragm at the bottom of the rib cage (which forms the top of the core). It is a significant and underappreciated generator of discomfort, pain, and dysfunction - yet can also be a powerful source of integrity, strength, vitality, and can give us a sense of being comfortably anchored or rooted in our bodies. In addition — and perhaps surprising to many readers — is that "the pelvic floor is an active sexual organ in women and men" [3] and is therefore essential to genital health and sexual function. It is richly supplied with nerve endings and is capable of generating a wide range of sensation from debilitating pain to intense pleasure.

Male Pelvic Floor Anatomy and Function

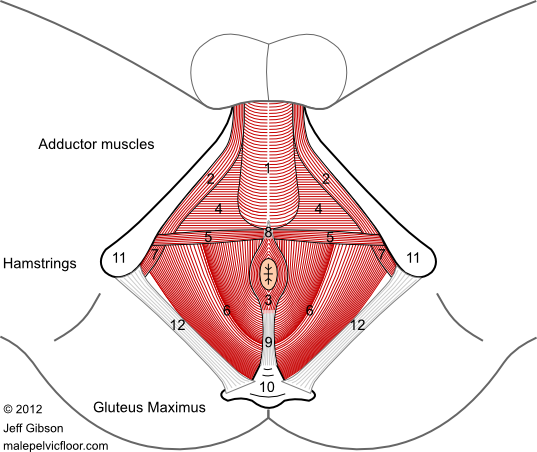

The pelvic floor muscles and connective tissues run from the pubic bone in the front (just above the genitals) to the tail bone (coccyx) in the back. Side to side they span the distance between the two bones that support your weight when sitting, commonly called the sits bones, or anatomically, the ischial tuberosities. These muscles are arranged in 3 layers, each of which has direct or indirect connections to the central perineal body (#8 in Figure 1, below) and the anal sphincters (#3), and they usually function together as a unit. The male pelvic floor has two openings: one for the urethra and one for the anus.

Fig. 1. Muscles of the pelvic floor, viewed from below

1. bulbospongiosus 2. ischiocavernosus 3. external anal sphincter 4. deep transverse perineal 5. superficial transverse perineal 6. levator ani 7. obturator internus 8. perineal body 9. ano-coccygeal ligament 10. tail bone (coccyx) 11. sits bones (ischial tuberosities) 12. sacro-tuberous ligament.

The Pelvic Diaphragm (deepest layer)

The pelvic diaphragm is bowl-shaped and is the largest, deepest, and most extensive layer of the pelvic floor. It is the only layer that completely fills, and thus closes off, the bottom of the core, which makes it the most relevant layer in terms of core support and function. It consists of the puborectalis, pubococcygeus, and iliococcygeus muscles — collectively known as the levator ani, which means 'lifter-of-the-anus' — plus the coccygeus muscle. As well as supporting the core from below, this muscle group helps maintain urinary and fecal continence, pulls or flexes the tailbone forward, assists in breathing, and cradles the prostate gland and the rectum.

The Urogenital Diaphragm (middle layer)

The relatively flat, often somewhat dense, and triangle-shaped urogenital diaphragm is the middle layer and spans roughly the front half of the opening at the bottom of the pelvis, with connections to structures that attach to the tail bone in the back. It provides a stable foundation that helps anchor and support the penile roots below it, the pelvic diaphragm and pelvic organs above it, and the anus behind it. One of the two urinary sphincters — and the only one which is under conscious control — is located here. This layer consists of the deep transverse perineal muscle and its associated fascial sheets, the external urinary sphincter, and by extension, the external anal sphincter and the ano-coccygeal ligament (also called the ano-coccygeal body), which together secure both this layer and the following superficial layer to the tail bone (coccyx) at the bottom of the spine.

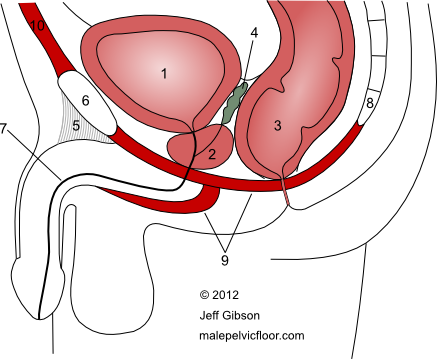

Fig. 2. The pelvic floor, genitals, and contents of the pelvic bowl, side view

1. bladder 2. prostate 3. rectum 4. seminal vesicles

5. suspensory ligament of the penis 6. pubic bone 7. urethra 8. tail bone

9. pelvic floor muscles (schematic)

The Genital Muscles, STPs, and EAS (superficial layer)

The genital muscles, superficial transverse perineals (STPs), and the external anal sphincter (EAS) form the most superficial layer of the pelvic floor and with the exception of the EAS are, like the urogenital diaphragm, located in the front half of it. The cylindrical or tube shaped bulbosponsiosus muscle (BS) and the paired ischiocavernosus muscles (IC) wrap around the three roots of the penis and have two main actions that greatly determine the rigidity and endurance of erections: compression of the penile roots (squeezing) and exerting a pull-back force (traction) on the connective tissues that surround the erectile chambers of the penis. Both of these actions are critical to erectile function as the former strongly pumps blood into the penis and the latter is crucial to the veno-occlusive mechanism that prevents blood from escaping. In this way, heightened tone and strong contractions of these muscles increase engorgement of the penis, making it harder, more pleasurably sensitive, and more resistant to potential injury during sexual activity. The bulbospongiosus has two additional roles: it rhythmically contracts at climax to propel the ejaculate, and it squeezes residual urine out of the urethra at the end of urination. When erect, contraction of the ischiocavernosus muscles lift the penis upward.

The paired STP muscles run side to side between the sits bones (ischial tuberosities) and merge into the central perineal body, where the fibers interweave with each other, with those of the bulbospongiosus muscle, and with the EAS — which itself extends to the tail bone via the ano-coccygeal ligament (ACL). Because of these shared fibers and continuities, the perineal body, the EAS, and the ACL, in a sense, function collectively as a long tendon that connects and anchors the penile bulb and bulbospongiosus to the bottom of the spine.

The external anal sphincter (EAS), which has subcutaneous, superfical, and deep divisions, helps maintain fecal continence. Excess tension in this oval-shaped muscle group, which generally correlates to overall pelvic floor muscle tone, can give rise to anal pain and voiding difficulties. Anal sphincter tone and the ability to consciously relax these muscles also greatly determines whether insertive anal sex is comfortable and successful. They are rich in nerve endings and therefore capable of generating a range of sensations from exquisite pleasure to intense pain. Recent research shows that while receptive anal sex has long been recognized as one option for gay male sexual expression, it is also a prevalent, under-reported, and increasing part of the sexual repertoire in the heterosexual population.

Two other muscles are worth noting: the obturator internus and the piriformis form the side and back walls, respectively, of the basin in which the pelvic floor is located. These muscles have close interconnections with the pelvic diaphragm, and the obturator internus provides an anchoring surface for two of the levator ani muscles as well as the pudendal canal, which is an important conduit for pelvic floor, genital, and anal nerves and blood vessels.

Are you wondering why I have not mentioned either the internal urinary sphincter (IUS) or the internal anal sphincter (IAS)? Technically, these muscles are not part of the pelvic floor and are more closely identified with the smooth muscles of the bladder (detrusor) and the rectum, respectively. The IUS muscle sits above the prostate gland, at the bottom of the bladder where the urethra begins (between #1 and #2 in Figure 2). The IAS muscle is a thickening of the end of the rectum, where it pierces the pelvic floor and the levator ani muscle group. Though neither of these are under conscious control, they have close associations and functional relationships with their consciously-controlled external counterparts and the larger pelvic floor muscles, and are responsive to both contractile forces and signaling messages that they generate.

The Male Pelvic Floor's Role in Genital, Pelvic, and Core Dysfunction and Pain

"I wanted to thank you for a great job. All of my [genital] pain is gone, including my groin pain."

The pelvic floor muscles and connective tissues can cause or contribute to pain, discomfort, or dysfunction occurring anywhere in the pelvic region or lower trunk: in the penis, urethra, testicles, epididymis, spermatic cord, perineum, prostate gland, anus, tailbone (coccyx), groin, inner thighs, sits bones, pubic and inguinal areas, lower abdomen, or low back. Quality of life can be significantly impaired, including sexual function, voiding, the ability to sit or move comfortably, and many others. These muscles often suffer from misuse, disuse, overuse, or abuse (trauma), which can result in clenching or excess tension, hyper-irritability, bracing, laxity or low tone, loss of elasticity and pliability, and the development of tender or trigger points which can cause local or referred pain, discomfort, irritation, or other altered sensation.

"I have more feeling, more function, and less pain [in the genitals and pelvic floor] since we started our work."

In cases of trauma — physical, psychological, or sexual — there can be a lack of connection, dulled or abnormal sensory awareness, lack of pleasure, or varying degrees of dissociation from the pelvis, pelvic floor, anus, and/or genitals.

Chronic Pelvic Pain Syndrome (CPPS), often misleadingly called chronic prostatitis (CP) or simply prostatitis, is a common diagnosis affecting millions of men in the U.S. alone — and the pelvic floor muscles are far too often overlooked or dismissed as generators, contributors, or perpetuators of the pain, discomfort, and dysfunction associated with CPPS. You can find much more information specifically on CP/CPPS on my malepelvicfloor.com website.

The Respiratory Diaphragm and its Relationship to the Pelvic Floor

In many ways, the respiratory diaphragm (RD) and the pelvic floor (PF) are mirror images of each other as they form the top (roof) and bottom (floor) of the core. The RD is a dome shaped muscle (two domes, actually) located deep under the rib cage, while the most extensive layer of the PF is bowl- or funnel-shaped and closes off the bottom of the pelvis.

"I've recently been feeling more aware of my breath reaching deeper into me, gently 'grabbing me' by the pelvic floor muscles, even in the absence of voluntary contractions. The feel of your initial manual evaluations of my muscle contractions was viscerally informative to me, and that has proven very helpful in this regard. Through purposeful breathing and contraction/release cycles, I am also trying to follow your advice to bring more vitality to the regions we explored."

These structures cap both ends of the abdominal cannister or tube, face each other, and can contract either simultaneously or alternately. Simultaneous contraction occurs when great physical effort is required such as in lifting weights or a heavy object. These co-contractions, along with concurrent abdominal and back contractions, increase the pressure within the abdominal cavity in such a way that the spine is stabilized and protected from injury during the activity. In normal respiration, the PF and RD have a reciprocal relationship; that is, when one contracts the other relaxes. This relationship can be used with good effect to mobilize the PF muscles and help them relax and stretch when they are too tight or clenched - just by using diaphragmatic breathing with awareness and intent. Specific positions and movements can further amplify the effects of the breath on the pelvic floor.

Diaphragmatic breathing can also shift the autonomic nervous system (ANS) from a sympathetic-dominant state to a parasympathetic-dominant state. This can have meaningful and significant effects, as these states contribute greatly to the status of our muscles. The sympathetic branch of the ANS tenses, tightens, and 'cocks' the muscles, preparing them to spring into action, while the parasympathetic branch relaxes, releases, and opens them. Discomfort, pain, muscular tension, and restricted range of motion are are common physical manifestations of the negative effect of chronic sympathetic over-stimulation. Such a state frequently accompanies so-called Type A personalities: those men who are constantly driven, always 'on', chronically stressed, and who often find it hard to relax, slow down, and let go. Core bodywork is an excellent way to shift the ANS from a sympathetic-dominant state to at least a more balanced or neutral state, and very often to a more parasympathetic-dominant state.

"It really works!"

(referring to diaphragmatic breathing's relaxing effect on both the pelvic floor muscles and the nervous system)

In these and other ways, attention to the breath and understanding the respiratory diaphragm's relationship to the pelvic floor can have multiple benefits across many domains. There are a number of ways to work with the RD - from bodywork to yoga to functional therapies to traditional resistance exercises - and I often suggest strategies and resources to my clients when appropriate.

Gordon and Reed have published a useful and recent literature review of the pelvic floor's relationship to the respiratory diaphragm [2], which may be of interest to some readers.

Giving the Male Pelvic Floor Muscles the Attention they Deserve

"I feel blessed and grateful to have a bodyworker such as you to work with. I feel healthier when I keep the pelvis and pelvic floor open."

It is clear that the male pelvic floor muscles should be given as much attention and emphasis as any other muscle group in settings that discuss or work with the core, including athletic facilities, yoga and martial arts studios, bodywork and other manual therapy clinics, print publications, and online discussions, to name a few. In addition, the pelvic floor muscles should be included — or at least considered — in any medical or health care evaluation of pelvic and genital pain syndromes, sexual dysfunction, or voiding issues. Sadly, and counter-intuitively, this is not usually the case.

"That exceeded my expectations - it was amazing. I would come back just for the pelvic floor work."

Men can benefit from becoming more familiar with their pelvic floor, understanding its contribution to their health and function, exploring it within a safe and supportive bodywork setting, and realizing that there are appropriate and effective manual therapy treatments available to them when they experience pain and dysfunction generated by, or related to, their pelvic floor muscles.

For more information and an expanded discussion of the pelvic floor, see my malepelvicfloor.com website.

References

1. Yuan X and Bevilaqua AC. Buttock Pain in the Athlete: the Role of Pelvic Floor Dysfunction. Current Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Reports. 2018; 6 (2): 147-155.

2. Gordon KAE and Reed O. The Role of the Pelvic Floor in Respiration: A Multidisciplinary Literature Review. Journal of Voice. 2018; pii: S0892-1997(18)30255-8. doi: 10.1016/j.jvoice.2018.09.024. [Epub ahead of print]

3. Raadgers M, Ramakers MJ, and van Lusen RHW, in The Pelvic Floor. Carriere B and Feldt CM, eds. Georg Thieme Verlag, 2006, page 400.